Skills Laundering: When Appearances of Skill Outshine Competence

- May 2025 Edition

- 8 mins

Executive Summary

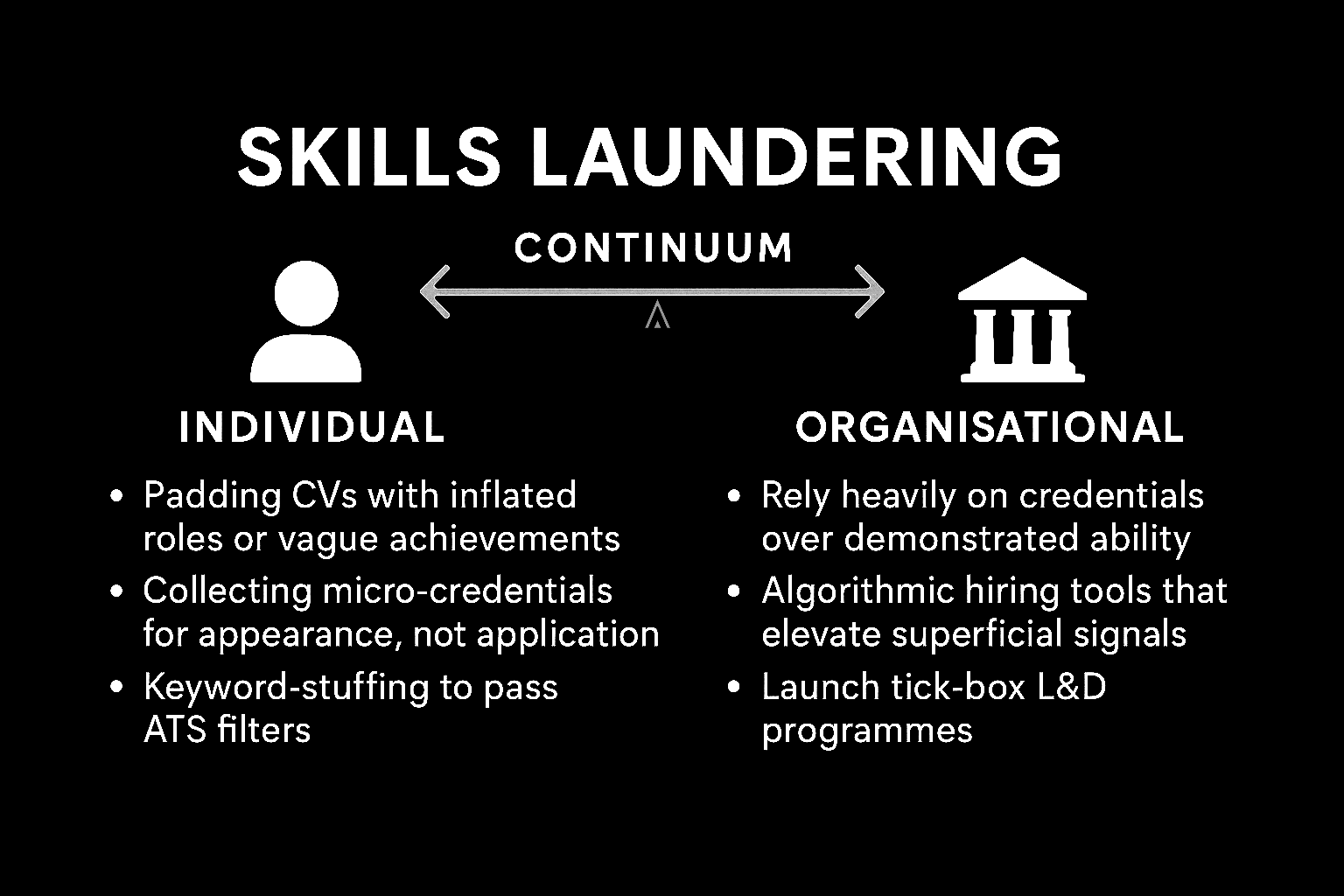

As organisations accelerate digital transformation and cultivate agile capability-building, a subtle but serious risk is manifesting: skills laundering. This phenomenon, where individuals disguise insufficient capability to make themselves appear professionally qualified, is silently undermining workforce development strategies. Fuelled by credential inflation, badge fatigue, AI-optimised hiring, and vanity metrics, skills laundering results in misinformed promotions, poor hiring outcomes, and eroded trust in learning systems.

This article explores the systemic drivers, manifestations, and organisational risks of skills laundering and what leaders must do to restore rigour to skills assessment and development.

The Illusion of Competence

Is it possible to look qualified, be promoted, and influence strategy without actually being skilled enough to do the job? That’s the uncomfortable truth behind skills laundering: the growing disconnect between what people seem to know and what they can actually do.

A disturbing trend is emerging, the misrepresentation or inflation of capability through certificates, rebranded titles, or AI-optimised profiles, often without the real skills to back them up. And it’s not just misleading. It’s operationally dangerous.

Defining Skills Laundering and Its Related Forms

At Aifa Consulting, we define skills laundering as the disguisement, misrepresentation or inflation of capability through credentials, titles, or curated profiles that mask the absence of real skill. It occurs when individuals appear workforce-ready but lack the applied competence to perform. While the phrase may have appeared in scattered commentary, our use of the term formalises its definition to encapsulate this growing phenomenon affecting global talent systems.

It shares characteristics with:

- Credential Inflation – Where more certificates or degrees are required or acquired without increasing true capability (LinkedIn)

- Badge Fatigue – The over-proliferation of digital credentials, leading to confusion and desensitisation among employers (Evolllution)

- Skills Signal Distortion – The unreliability of titles, endorsements, or CVs optimised for algorithms to reflect real-world ability. An applicant might stuff their CV with trendy terms to pass an algorithmic filter, prioritising appearance over substance, effectively “laundering” their skills profile to look clean and impressive.

The result? Individuals who appear highly skilled, but whose capabilities are untested or shallow and organisations that struggle to differentiate substance from style.

Systemic Drivers Behind the Trend

1. The Persistence of Degree Bias

Even where degree requirements have been formally removed, a preference for traditional academic pathways persists. According to Harvard Business School’s Managing the Future of Work project, 75% of middle-skill hires still hold degrees—revealing deeply ingrained hiring biases. (HBS Podcast, 2024).

2. Over-Reliance on AI-Based Recruitment

Applicant tracking systems (ATS) and AI screeners reward keyword-heavy CVs. As a result, candidates pad resumes with job description phrases or manipulate formatting to pass filters. Harvard’s study revealed these systems routinely reject viable candidates for minor mismatches. (Euronews).

3. Superficial Learning Metrics

Organisations frequently measure learning by hours logged or badges earned. Yet a 2023 edX/Workplace Intelligence survey found that 51% of executives believe their L&D programmes are ineffective (Worklife News). Logging hours isn’t enough!

4. Title Inflation and Rebranding

5. Exclusion of Non-Traditional Talent

A Quiet Compromise in Control: The Auditor Who Slipped Through the Cracks

The Internal Audit team had been running lean for months. With regulatory reporting timelines looming, the arrival of a new team member, certified, well-spoken, and referred by a trusted colleague was a relief.

His CV was polished: a Certified Internal Auditor badge, a string of related courses, and a confident grasp of compliance jargon during interviews. He handled his onboarding efficiently, spoke fluently in meetings, and seemed to navigate the systems with ease. By the second month, his confirmation was already in motion.

Then came his first full audit assignment. His report, though well-formatted, raised subtle flags. The testing procedures lacked depth. Risk ratings were conservative but unsubstantiated. He referenced frameworks, but missed how they applied in context. When asked to walk through his sampling rationale, he deferred to templates. Internally, the team began quietly revalidating his findings.

He wasn’t disengaged, he was overestimated. His credentials had passed through recruitment filters unchecked. No working simulations. No walk-through of past audits. The confirmation process prioritised speed over scrutiny, highlighting how organisational urgency can blur critical judgment.

His case exposed how easily skills laundering can hide in plain sight, especially when systems reward polish over performance and progression is assumed rather than earned.

Organisational Risks of Skills Laundering

- Performance Gaps – Employees underperform when their credentials exceed their capabilities.

- Erosion of Trust in Credentials – Hiring managers become sceptical when too many credentials lack rigour.

- Misallocated L&D Investment – Completion-based metrics do not guarantee capability gains.

- Talent Blind Spots – Organisations overlook unconventional candidates who may offer the best-fit capabilities.

How Organisations Can Respond

1. Adopt Skills-Based Hiring and Assessment

Move from credentials to competence. Use simulations, case-based interviews, and work samples. The SHRM Foundation recommends going beyond badges to assess skill mastery. Companies like Google, for example, have used work sample tests in lieu of over-focusing on degrees, to ensure substance.

2. Map Credentials to Competency Frameworks

Organisations should explicitly define the skills and behaviours needed for each role, so they can better evaluate if a given credential or course actually imparts those. According to Doris Savron of University of Phoenix, Micro-credentials only become “meaningful currency” in the talent economy when they are mapped to workforce needs, reliably assessed, and transparently communicated. (Evolllution).

3. Raise the Bar for Credential Standards

4. Refocus L&D on Application, Not Optics

Shift from vanity metrics (hours trained, badges earned) to impact metrics (performance improvements, innovation sparked by new skills). Curate learning paths more thoughtfully. Instead of encouraging employees to earn as many badges as possible, guide them to a few high-quality certifications or projects that fill true skill gaps. Provide opportunities to apply new skills on the job (through stretch assignments, cross-training, etc). As Trena Minudri of Coursera notes, executives only trust L&D when it delivers business-relevant skills. (Worklife News).

5. Redesign Promotion Practices

6. Watch for Organisational Enablers

Audit your systems to check whether they:

- Reward credentials over contributions?

- Filter out high-potential but unconventional candidates?

- Inflate job titles without upskilling to match?

Recognising Competence Beyond Credentials

Organisations and individuals alike benefit from validation that goes beyond internal recognition. Global awards and peer-reviewed platforms help distinguish professionals who deliver measurable impact not just credentials.

Professional bodies such as:

- CIPM – HR Best Practice Awards (Nigeria/Africa)

- CIPD – People Management Awards (UK/international)

- CIPS – Global Excellence Awards (International)

- CQI – International Quality Awards (ISO, quality leadership)

- Others including SHRM, PMI, ISACA, and many more reputable ones.

These platforms reflect excellence in action. When individuals are encouraged to pursue them, it reinforces a culture that values applied skill, problem-solving, and business relevance not just decorated profiles.

From Optics to Outcomes

Skills laundering is a by-product of systems that reward what’s visible rather than what’s valuable. The solution isn’t to abandon credentials—but to reposition them as indicators that require validation

Substance must matter more than signals. As organisations strive for agility, innovation, and equity, the real question isn’t whether skills laundering exists but whether your systems are enabling it.

At Aifa Consulting, we are committed to shedding light on the nuanced challenges of skills laundering. By formally defining and addressing this phenomenon, we aim to help organisations design talent systems that distinguish genuine capability from curated appearances.

References

- Millerd, P. (2020, July 16). Degree Inflation & The Fake Talent Gap. LinkedIn

- Savron, D. (2025, April 15). Microcredentials: Revolutionizing Higher Education or Creating Chaos? The EvoLLLution.

- Harvard Business School (2024). Managing the Future of Work Podcast: Joseph Fuller on The Gartner Talent Angle. HBS

- Berjikian, K. (2023, August 14). How AI is filtering millions of qualified candidates out of the workforce. Euronews

- Mensik, H. (2023, November 9). Why everyone is lacking confidence in L&D programs. WorkLife News

- Credential Engine. (2022). Counting U.S. Postsecondary and Secondary Credentials. Credential Engine

- SHRM Foundation (2021). Making Skilled Credentials Work. SHRM

Note: While the term “skills laundering” is emerging, Aifa Consulting acknowledges that it may have been referenced elsewhere in informal commentary. However, based on current research and analysis, we use this term to anchor a structured, evidence-informed narrative that highlights how workforce signals can distort real capability. This insight reflects Aifa’s independent synthesis of related trends and terminology shaping the future of talent strategy.